MANDALAY. The Irrawaddy River. Yangon, formerly Rangoon. Wonderfully evocative names, aren’t they? I think of heat rising from the banks of a wide river; golden, towering pagodas; and bustling street markets colour dashed and culture steeped. But I also think of elephants tugging timber, workers loading steamers and men in linens drinking gin & tonics on hot, hot nights. Burma existed in my imagination – exists even now, having been there – as much as a product of Empire as a product of Asia. In Yangon, the buildings of Empire are all still there, decaying, repurposed, divided, lived in, empty, rat filled; all of the above, all at once. How to square splendour and decay, empire’s legacy and Burma’s future – my own sense of being British with the tragedy of what happened here, is happening here?

Yeah, I like setting myself up to fail.

As I’ve recounted in a previous post, we arrived in Yangon from Tokyo (could two cities ever be so different?). The streets were thick with traffic – banged up cars, buses without doors, and scooters that had seen better days. And it was hot. Heat rose in waves from the asphalt, forcing its way into the cracks in the road, the spaces where your skin touched your clothes and the opening-closing gaps between your heels and your flip flops. Brow mopping was de rigeur, parasols mandatory – unless you were white, in which case you just baked and sweated, and generally brought the shabby elegance of the place down, letting it drip off your hair and run down your neck. People sat in tea shops and on street corners, seeking shade wherever they could. Old women sat on the pavement selling mangoes, a man stood at a stall preparing betel nuts to chew for the taxi drivers that pulled up at the side of the road.

A seamstress in Yangon’s central market, Bogyoke Market (or Scott Market as it was known under British rule).

I had a cold – a rotten, clingy affair that made me sniffle whilst I shuffled along the busy streets, cursing my preponderance of snot that seemed so out of place in such tropical climes, regretting that I hadn’t offered BK-C more sympathy when she had suffered from the same thing in Japan but ten days before. I spent one day cossetted in bed in the hostel, thankful for the air conditioning but cursing the frequent power cuts. The rest of the time we spent wandering the streets.

The Sule Pagoda is an important, sacred site for Buddhists and a defining landmark of downtown Yangon. A pagoda has been on that site for centuries, and parts of the current structure date back to the fifteenth century. Demonstrating their usual regard for Other Peoples’ Cultures, when the British arrived they built a roundabout around the pagoda, which remains today. Beat that, Swindon.

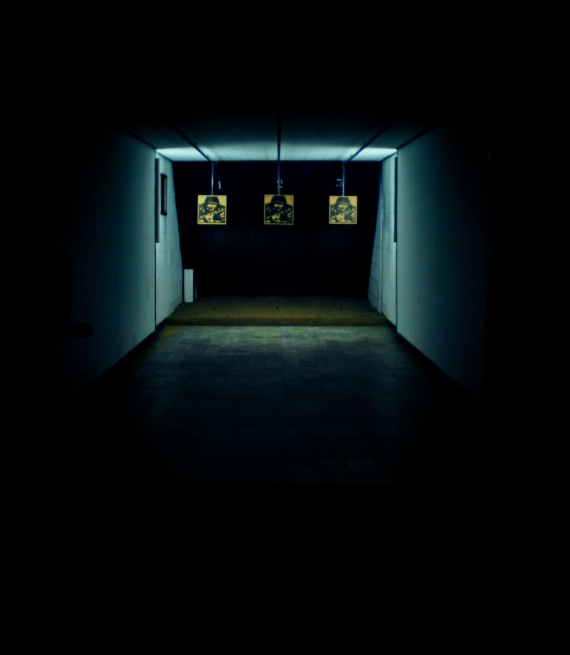

WE VISITED THE famous Shwedagon Pagoda, the iconic landmark of the city that is a must see for visitors. Or we tried to, anyway. It was early evening, our intention having been to get there to witness the setting sun reflected on its golden spire, but having failed to appreciate how long it would take to walk there. On the way, walking up Shwedagon Pagoda Road, we’d passed grand old colonial houses lining the street, most behind barbed wire and with expensive looking cars outside, a few run down and abandoned. By the time that we arrived, the sun had already dipped beyond the horizon. We left our shoes at an overmanned desk at street level and walked up the wide, grand corridor that leads to the entrance of the Pagoda. There were a handful of other tourists ambling alongside us, as well as a few small groups of Indian naval officers and sailors in spotless, perfectly creased white trousers and shirts. As we’d walked around the city earlier in the day, we’d seen dozens of the sailors in the markets, shops and streets, as well as clustering around ATMs, arguing about the exchange rate. When we reached the entrance to the Pagoda itself there was a desk, behind which sat two officials. One looked at us and tapped a sign that said Entry for Foreigners: 8,000 Kyatt. That’s $8 or about £5. Not a huge amount by my own reckoning – probably what I’d pay for a beer in London – but it was a steep price by Burmese standards, and money that goes entirely to the military junta. Plus, we were on a budget. No doubt, though, we would have paid and gone in if, at that moment, two of the Indian Navy guys hadn’t strolled past the desk unchallenged.

“Aren’t you going to charge them as well?” I asked.

“No.”

“But they’re foreigners, too. Look,” I said, pointing, “they’ve even got the Indian flag stitched to the arms of their shirts.”

The official looked at me, blinked once. “Yes,” he said, “but they’re officers.”

“Well how do you know that we’re not officers?”

“Are you?”

“…no.”

So we left in an indignant huff, railing against the unfairness of the situation but also feeling a little bit self-righteous because we’d refused to give our money to the Government, money that either went into the pockets of generals or funded state repression of the Myanmar people. I’m sure that the Indian officers had a lovely time at the Shwedagon Pagoda, though.

So this is the night time view from Vista Bar. Much better to enjoy the pagoda with a drink in your hand than pay to go in. Right?

ON OUR FINAL day in Yangon, we went on what must have been one of the best walking tours we’ve ever done, with Free Yangon Walks. The tour (which consisted of just us) was led by an Australian, Gino, the confident, garrulous, remarkable founder of this enterprise (when we took the tour with him it was his first week and he was the sole guide, offering free walks every day). Gino showed us many of the old buildings and took us through the history of each, as well as offering an insight into the broader history of Burma.

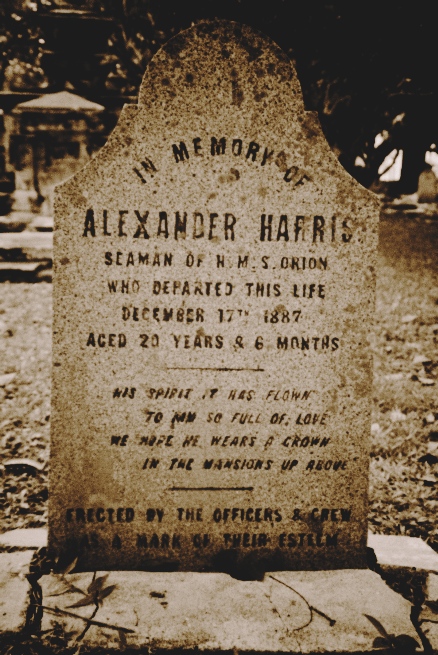

Having exhausted its own forests of oak, Britain wanted Burma for its teak. Without wood, the Royal Navy wouldn’t have its ships. And without ships, Britain wouldn’t have its empire. So over the period of 60 years and three wars, the British conquered the country; by 1886 the whole of Burma was administered as a part of India. With the timber companies came banks, hotels, and office buildings, along with investment in the country’s infrastructure. Not that the infrastructure needed to ship teak from the north to the south was particularly sophisticated. Felled trees were dried and then piled up in the dry season by the side of rivers; when the rainy season came, they were floated downriver, until they reached the wide expanse of the Irrawaddy. There, they were lashed together into giant, makeshift rafts that men lived aboard and piloted down to the shipping and timber merchants of Yangon.

Walking along Yangon’s riverfront and the streets leading up to it, those buildings are still there, the paint peeled, the brickwork fallen away, and the floors – still tiled with beautiful, nineteenth century tiles made in the long dead factories of Manchester and Stoke-on-Trent – are stained with the red marks of betel nut, where chewers have spat. The flooring alone of some of those buildings is probably now worth millions of pounds. For the most part, people live, work and walk upon them in poverty.

The Burmese people – or, more correctly, the patchwork of different ethnic groups that occupy modern day Myanmar, the largest of which are called the Bamar, whom Burma was named after – are culturally distinct from the Siamese to the north and east, now in modern day Thailand, along with the Chinese and Indian groups that they share borders with. Prior to British rule, the literacy rate in the country was remarkably high for that time, at 60% (compared to about 75% in Britain), and there was a thriving culture of writing and theatrical performances. Even today, the Burmese love to read, and all along our travels in Myanmar we saw stalls selling used books in Burmese. This might not sound odd, but it stands apart from most other places we’ve visited in South East Asia. In Laos, for instance, a comparably poor country, there is no tradition of reading, and very few Laotians read for pleasure.

SO THE BRITISH came and built the stunning buildings that I enjoyed seeing as a tourist, giving me the thrill of seeing something so British somewhere else, so out of place, and they built railways and roads and schools, and educational opportunities for women increased enormously (literacy rates among women were about 5% previously)… but of course the British also played ethnic groups against one another in order to maintain control, brought institutional racism, put down rebellions with bloody massacres and, naturally, shipped a large portion of the country’s natural resources to Britain for fat profits.

In George Orwell’s Burmese Days, his novel based upon his experiences as a colonial policeman in Burma, the characters are all venal, selfish, destructive people that lord over the locals as well as making each others’ lives hell. Empire corrupts and damages everything, including the imperialists themselves. This all encompassing corruption is also mirrored in Amitav Ghosh’s excellent novel about colonial Burma, India and Malaysia – The Glass Palace. The British sit in their teak camps pining after the rolling fields and craggy highlands of their home, drinking and worrying about when they’ll die of malaria.

Before Burma gained independence in 1948 things looked like they might work out alright because of a driven, charismatic, inclusive leader called Aung San – the father of Aung San Suu Kyi. Unfortunately, he was murdered by political rivals in 1947. The country then limped along as a Republic, still riven by ethnic infighting, until the military coup in 1962 gave the country the repressive junta that still rules it today.

Throughout our time in Burma, I felt uncomfortably colonial. Every time we walked into a hotel or hostel reception, the trio of beautiful Burmese women who were inevitably sat behind the desk always stood, and remained standing the entire time I was in the room. “Please, sit down,” I’d entreat them, but they never listened. We asked a postcard seller that we spoke to what Burmese people thought of the British (he initiated the conversation on politics – more on that in a future post). “I’m scared to tell you,” he said. I pressed him, and he told us that “Burmese people, they are afraid of two people: the British, and the Japanese.” When we visited the cooler, mountain climes of Pyin Oo Lwin (or “the hill station,” after its imperial designation, as it’s still known), there were punnets of strawberries for sale everywhere, and lots of stalls were selling jams and fruit wines. It was all weirdly familiar, comforting and uncomfortable, all at once.

SO: AS A RESULT I’ve been struggling recently with my sense of national identity. These are the kind of existential indulgences that one embarks upon when taking a year off work. Here’s the thing: the British really screwed over Burma – and a load of other places – but my own sense of Britain and its place in the world, as being active in world politics, as being a multi-cultural nation with links across the globe, as being – in some sense – a good thing, is predicated upon this history of Empire. Also, I might add, the impending referendum on Scottish independence is playing into my general anxieties. What’s British if a part of it leaves? Those people building the banks and railways in Burma were Scottish and Welsh as well as English. Not a history to be celebrated, but it is a shared history.

Looking up at those impressive, familiar colonial buildings in Burma (and Malaysia) it’s easy to forget the bloodshed and hatred that went alongside them, and just to feel excited as I experience a strange sense of belonging, like seeing my own history reflected back from an unexpected place. Weird isn’t it? There’s a whole body of academic studies on this, of course, called postcolonialism and this kind of musing doesn’t really stand up to any kind of academic scrutiny – but equally the sensation of seeing yourself reflected in the remnants of Empire can’t quite be captured in a beautifully footnoted, double spaced essay.

Britain isn’t empire, but a sense of nation can encompass the bad with the good, conflict with agreement, making something that’s worthwhile today, without having to forgive, accept or condone the things in the past that would fall far short of the nation today. The challenge, for Britain, is to build something out of all these pieces.

In The Glass Palace, towards the end of the book, one of the Burmese characters talks about why he believes Aung San Suu Kyi will work for Burma:

“[…] she’s the only one who seems to understand what the place of politics is… what it ought to be… that while misrule and tyranny must be resisted, so too must politics itself… that it cannot be allowed to cannibalise all of life, all of existence. To me this is the most terrible indignity of our condition – not just in Burma, but in many other places too… that politics has invaded everything, spared nothing… religion, art, family… it has taken over everything… there is no escape from it… and yet, what could be more trivial in the end?”

So, I can’t say that I’ve found any answers to my existential questions. But I can say that sometimes we find parts of ourselves in the most unexpected places. And, also, that I will be very sad if Scotland leaves the United Kingdom.

This post was written and uploaded in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia.

NEXT TIME: More Burma, less Britain.